LnRiLWZpZWxke21hcmdpbi1ib3R0b206MC43NmVtfS50Yi1maWVsZC0tbGVmdHt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmxlZnR9LnRiLWZpZWxkLS1jZW50ZXJ7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWZpZWxkLS1yaWdodHt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOnJpZ2h0fS50Yi1maWVsZF9fc2t5cGVfcHJldmlld3twYWRkaW5nOjEwcHggMjBweDtib3JkZXItcmFkaXVzOjNweDtjb2xvcjojZmZmO2JhY2tncm91bmQ6IzAwYWZlZTtkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1ibG9ja311bC5nbGlkZV9fc2xpZGVze21hcmdpbjowfQ==

LnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfSAud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UudGItaW1hZ2VbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZT0iMzQwMmY5OWM0ZGRhYjU2MmY3Zjc5M2E1MzJhY2FlNzIiXSB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAwJTsgfSAudGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAgLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfSAud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UudGItaW1hZ2VbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZT0iNjVjMjcyMTQ3ZDZjZDY1OWUyN2ZlOGNlNmY1ZmY5NGUiXSB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAwJTsgfSAgQG1lZGlhIG9ubHkgc2NyZWVuIGFuZCAobWF4LXdpZHRoOiA3ODFweCkgeyAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gIC50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gIH0gQG1lZGlhIG9ubHkgc2NyZWVuIGFuZCAobWF4LXdpZHRoOiA1OTlweCkgeyAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gIC50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gIH0g

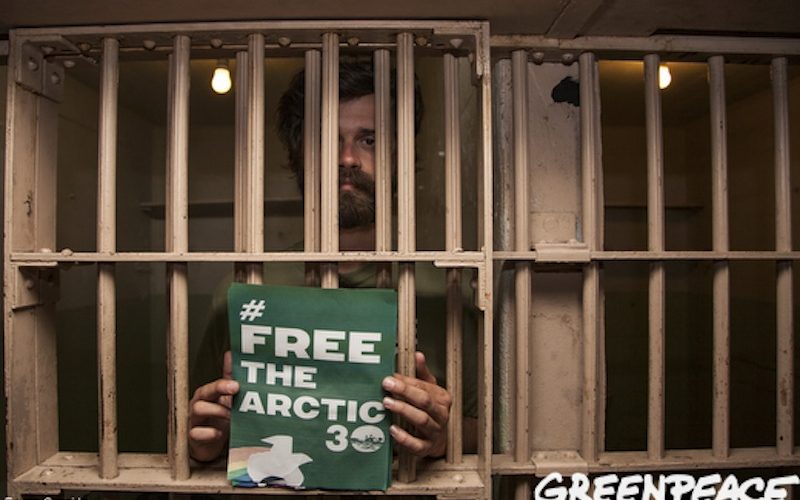

As head of media for Greenpeace International, British author Ben Stewart played a critical role in the saga of the Arctic 30, the Greenpeace activists who were charged with piracy and imprisoned for protesting oil drilling in the Russian Arctic by state-owned company Gazprom. He oversaw the massive global campaign that sought the protesters’ release and has written a book about the ordeal.

As head of media for Greenpeace International, British author Ben Stewart played a critical role in the saga of the Arctic 30, the Greenpeace activists who were charged with piracy and imprisoned for protesting oil drilling in the Russian Arctic by state-owned company Gazprom. He oversaw the massive global campaign that sought the protesters’ release and has written a book about the ordeal. I spoke with him via Skype in May as he was beginning his book tour in Vancouver. Our conversation centred on the role civil society and popular culture can play in effecting environmental change. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Kelley Tish-Baker: Were there any repercussions for the three Arctic Sunrise Russian activists after they were released from their months of imprisonment?

Ben Stewart: They’re not out of the woods yet, in that they live in a country where they’re marked down effectively as dissidents. You know, we’re not still in the Soviet era, but nevertheless, Putin’s government announced a couple of weeks ago they’re going to put restrictions on NGOs, and brand NGOs like Greenpeace and Amnesty as foreign agents. This is a long game.

It’s easy, I would suggest, for people who returned to Britain and the other countries. They never have to go back to Russia, and I think probably most of them don’t have a great desire to go back. But others of them remain in a relatively precarious position, as do the others who worked at the Greenpeace office then. They were heroes during this saga. They were told by their relatives, “Get out. Don’t continue working for them.” And they are now on the wrong side of a government that’s showing increasingly totalitarian tendencies.

What about those average Russian citizens who signed the petition in such huge numbers?

It’s not like the authorities have gone around picking them up – there were 30,000 of them. But it is remarkable in that they have effectively registered with their telephone numbers, their addresses and their names in huge numbers, saying, “I oppose this.” I don’t think that now is the moment there’ll be repercussions from that, but I don’t think it’s unreasonable to suggest that Russia could take a turn even further towards a totalitarian form of government. And who knows where that goes for the people involved in the saga.

With countries like Russia, we’re perhaps not so surprised when they clamp down on NGOS. But in India, the world’s largest democracy, what prospects are there for civil society when they do so? I understand the Indian government just froze Greenpeace India’s bank accounts and suspended your registration there.

I just got back from there. I worked there for four months on that case. There’s a shrinking space for civil society groups. The Modi government has shown some pretty concerning tendencies. We sometimes imagine that we’re on this unstoppable trajectory towards global, progressive, liberal governments. And actually, we win sometimes [but other times] we lose ground. And that’s what’s happening in Russia and in India at the moment. We should not assume at all that there will be some natural rolling back, and the pendulum will swing again and that we will regain this ground. Governments have a tendency to try to take space from civil society groups who criticize them. And we have to fight to maintain that space.

How effective can civil society groups be in effecting change when even democratic governments are not just unresponsive to it, but actively hostile towards it?

It’s more difficult to manufacture consent than it previously was, partly because of social media. It’s easier to point to the Emperor and say he’s got no clothes nowadays. So at the same time as democratic space shrinks, other areas open up to us. This is not the moment to raise the white flag. This is the moment to recognize that that’s what’s happening because we are now the opposition. I mean, that’s what’s happening in India. The Congress Party is nowhere and so the Modi government sees civil society as the opposition. Take it as a compliment and mobilize and get busy.

I’m looking forward to the film version of the book. When do you think it will be out?

I think (producer David) Puttnam wants to take it to Cannes in 2017. It’s a long journey but it will be worth it. I think culture is very, very important in breaking open issues and shifting attitudes and I don’t think there’s been a great climate change movie made before. There’ve been some good documentaries. But filmmakers avoid it. They make “Interstellar” about a dystopian planet so ravaged by environmental disaster so that they need to leave, and they won’t mention climate change. The Road, by Cormac McCarthy – it’s basically a climate change novel but they don’t mention climate change. It’s seen as this toxic thing that’s going to drive viewers away. Well you can’t avoid it in this film. If they can make this a really good climate change film it will be a first, and that’s quite exciting.

Read our review of the Ben Stewart book Don’t Trust, Don’t Fear, Don’t Beg: The Extraordinary Story of the Arctic Thirty