LnRiLWZpZWxke21hcmdpbi1ib3R0b206MC43NmVtfS50Yi1maWVsZC0tbGVmdHt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmxlZnR9LnRiLWZpZWxkLS1jZW50ZXJ7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWZpZWxkLS1yaWdodHt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOnJpZ2h0fS50Yi1maWVsZF9fc2t5cGVfcHJldmlld3twYWRkaW5nOjEwcHggMjBweDtib3JkZXItcmFkaXVzOjNweDtjb2xvcjojZmZmO2JhY2tncm91bmQ6IzAwYWZlZTtkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1ibG9ja311bC5nbGlkZV9fc2xpZGVze21hcmdpbjowfQ==

LnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfSAud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UudGItaW1hZ2VbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZT0iMzQwMmY5OWM0ZGRhYjU2MmY3Zjc5M2E1MzJhY2FlNzIiXSB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAwJTsgfSAudGItZ3JpZCwudGItZ3JpZD4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWlubmVyLWJsb2Nrcz4uYmxvY2stZWRpdG9yLWJsb2NrLWxpc3RfX2xheW91dHtkaXNwbGF5OmdyaWQ7Z3JpZC1yb3ctZ2FwOjI1cHg7Z3JpZC1jb2x1bW4tZ2FwOjI1cHh9LnRiLWdyaWQtaXRlbXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOiNkMzhhMDM7cGFkZGluZzozMHB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbntmbGV4LXdyYXA6d3JhcH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4+Knt3aWR0aDoxMDAlfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLXRvcHt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtc3RhcnR9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uLnRiLWdyaWQtYWxpZ24tY2VudGVye3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7ZGlzcGxheTpmbGV4O2FsaWduLWNvbnRlbnQ6Y2VudGVyfS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWJvdHRvbXt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmZsZXgtZW5kfSAgLnRiLWltYWdle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LndwLWJsb2NrLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS5hbGlnbmNlbnRlcnttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvO21hcmdpbi1yaWdodDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZSBpbWd7bWF4LXdpZHRoOjEwMCU7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87d2lkdGg6YXV0bzt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2V7ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9ue2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGUtY2FwdGlvbjtjYXB0aW9uLXNpZGU6Ym90dG9tfSAud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UudGItaW1hZ2VbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZT0iNjVjMjcyMTQ3ZDZjZDY1OWUyN2ZlOGNlNmY1ZmY5NGUiXSB7IG1heC13aWR0aDogMTAwJTsgfSAgQG1lZGlhIG9ubHkgc2NyZWVuIGFuZCAobWF4LXdpZHRoOiA3ODFweCkgeyAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gIC50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gIH0gQG1lZGlhIG9ubHkgc2NyZWVuIGFuZCAobWF4LXdpZHRoOiA1OTlweCkgeyAudGItaW1hZ2V7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0ud3AtYmxvY2staW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLmFsaWduY2VudGVye21hcmdpbi1sZWZ0OmF1dG87bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0OmF1dG99LnRiLWltYWdlIGltZ3ttYXgtd2lkdGg6MTAwJTtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bzt3aWR0aDphdXRvO3RyYW5zaXRpb246dHJhbnNmb3JtIDAuMjVzIGVhc2V9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZXtkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlfS50Yi1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbi1maXQtdG8taW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb257ZGlzcGxheTp0YWJsZS1jYXB0aW9uO2NhcHRpb24tc2lkZTpib3R0b219LnRiLWdyaWQsLnRiLWdyaWQ+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1pbm5lci1ibG9ja3M+LmJsb2NrLWVkaXRvci1ibG9jay1saXN0X19sYXlvdXR7ZGlzcGxheTpncmlkO2dyaWQtcm93LWdhcDoyNXB4O2dyaWQtY29sdW1uLWdhcDoyNXB4fS50Yi1ncmlkLWl0ZW17YmFja2dyb3VuZDojZDM4YTAzO3BhZGRpbmc6MzBweH0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW57ZmxleC13cmFwOndyYXB9LnRiLWdyaWQtY29sdW1uPip7d2lkdGg6MTAwJX0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi10b3B7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LXN0YXJ0fS50Yi1ncmlkLWNvbHVtbi50Yi1ncmlkLWFsaWduLWNlbnRlcnt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6ZmxleDthbGlnbi1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcn0udGItZ3JpZC1jb2x1bW4udGItZ3JpZC1hbGlnbi1ib3R0b217d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmZsZXg7YWxpZ24tY29udGVudDpmbGV4LWVuZH0gIC50Yi1pbWFnZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOnRyYW5zZm9ybSAwLjI1cyBlYXNlfS53cC1ibG9jay1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UuYWxpZ25jZW50ZXJ7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0bzttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2UgaW1ne21heC13aWR0aDoxMDAlO2hlaWdodDphdXRvO3dpZHRoOmF1dG87dHJhbnNpdGlvbjp0cmFuc2Zvcm0gMC4yNXMgZWFzZX0udGItaW1hZ2UgLnRiLWltYWdlLWNhcHRpb24tZml0LXRvLWltYWdle2Rpc3BsYXk6dGFibGV9LnRiLWltYWdlIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1jYXB0aW9uLWZpdC10by1pbWFnZSAudGItaW1hZ2UtY2FwdGlvbntkaXNwbGF5OnRhYmxlLWNhcHRpb247Y2FwdGlvbi1zaWRlOmJvdHRvbX0gIH0g

We complain all the time about the global treatment of renewable energies as we move from fossil fuels to renewables. It’s taking too long. We need a better energy mix. The subsidies are unfair. But we don’t really question the inevitability that the future belongs to renewable energy. After all, fossil fuels are certain to run out sooner or later.

But what if they don’t run out? Under what conditions does the future belong to renewables?

A Japanese breakthrough may force the answer upon us.

We complain all the time about the global treatment of renewable energies as we move from fossil fuels to renewables. It’s taking too long. We need a better energy mix. The subsidies are unfair. But we don’t really question the inevitability that the future belongs to renewable energy. After all, fossil fuels are certain to run out sooner or later.

But what if they don’t run out? Under what conditions does the future belong to renewables?

A Japanese breakthrough may force the answer upon us.

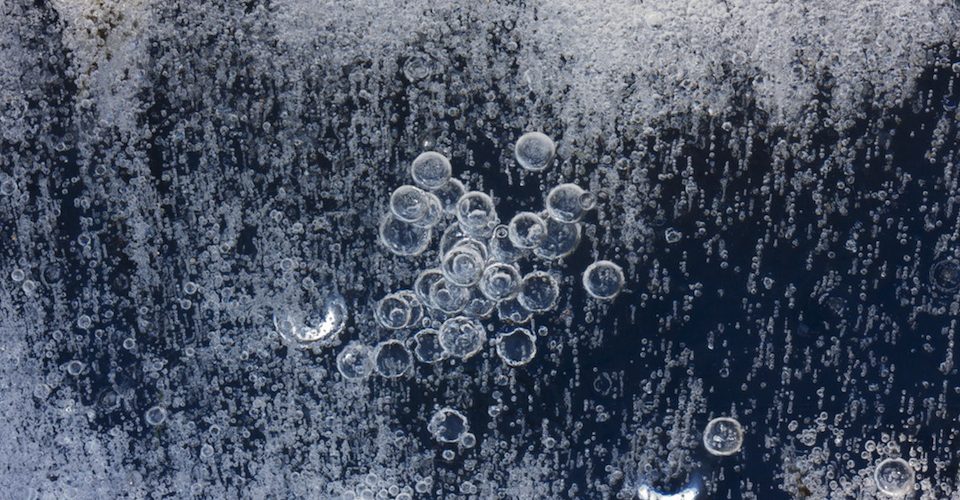

Methane hydrates are methane trapped in water under the ocean floor. Several weeks ago, energy researchers in Japan figured out how to a) extract and b) burn this methane. Also known as “fire ice,” the methane can be converted into natural gas.

A neat trick, and they weren’t doing it just to see if they could, either. Though commercial extraction is still years from being possible, Japan’s National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology thinks there is enough gas in Japanese waters to power the island country for 100 years.

Not to be outdone, the United States Geological Survey estimates that the world’s gas hydrates “may contain more organic carbon than the world’s coal, oil, and other forms of natural gas combined.” In other words, there’s an untapped fossil fuel out there in impressive quantities.

The US, incidentally, has already run a successful test off the coast of Alaska. “Energy independence” has been on the lips of American politicians since the oil crisis of the 1970s and an untouched supply of extractable fuel will not go unnoticed in Washington if further tests come back with positive results.

Of course, even those massive reserves of methane will eventually run out, but that’s really beside the point. Burning it all – or rather, burning it all instead of using renewable energies – will likely push global warming past the point of no return while further delaying the emergence of renewables as the world’s primary energy source.

Many governments around the world have been at least paying lip service to the idea that renewables will eventually take over from the coal, oil or gas on which most states currently rely. It has been a relatively easy decision to make, given that even the most optimistic predictions show a steady decline in global fossil fuel reserves, and it’s impossible to discern whether the shift can be traced to changing environmental attitudes or old-fashioned political realism – an adherence to narrowly defined self-interest.

If realism takes over, and if “fire ice” is anywhere near as plentiful as scientists think it is, then it may not be hyperbole to say that the climatic future will come down to a simple matter of cost-effectiveness: can renewable energy be produced for less money than hydrate methane? It remains unknown how cheaply “fire ice” can be extracted. If the cost is significantly higher than that of wind or solar energy then renewables may yet win the day.

All things being equal, renewable energy has the inside track as our next big energy source. It’s plentiful, getting cheaper all the time and supported by large segments of the population. Against diminishing quantities of fossil fuels, renewables have been making steady gains. Will these gains continue if renewable energies are thrown into a cage match with a massively plentiful new fuel? Have we been kidding ourselves in thinking that the world has seen the environmental light? Or would it come down, as it has so many times in history, to the unsentimentality of classical economics?

Cross your fingers that we don’t have to find out.

To see a video of methane plumes being set on fire and to learn about why methane release could be so devastating to the planet, check out the A\J article Rising Giant from the Lifecycles issue.