LIFE IS DEFINED through success and failure, often in the same breath. The most successful still feel they could have done more, and even the poorest among us can be content.

LIFE IS DEFINED through success and failure, often in the same breath. The most successful still feel they could have done more, and even the poorest among us can be content. In the same way, the global movement for sustainability is a story of pockets of success within the failure to curtail our ever-increasing demand for resources and wealth.

In a year of travel, we saw many of the failures in growth and development, but even more examples of how people and countries have risen to the challenge. We saw snapshots of people making a living, contributing to their family and community, and of the values and faith that underpin their actions.

A year is not a long time if you plan to see the world, but it is enough time to gain impressions, draw links and find common themes. Enough time to catch glimpses of what works and what doesn’t, and to cobble together an understanding of common threads and a few ideas for what can be done.

FIVE LESSONS

Distilling our experiences through Europe, India, Southeast Asia, and Australia, these are the five most important things I have learned:

1. There is no hope.

Sustainability is a myth. Our current global economy is unsustainable and unstoppable in its drive to develop the last resources. Whether through greed or need, we will be hard pressed to save what remains once we have used up what we have. Small actions multiplied by 8 billion people, combined with the acquisitions and actions of large multinationals, ensure that the long term outlook is bleak.

2. There is hope.

There is always hope. The drive for a better life is the goal common to all people in all countries. The depth of commitment of people and organizations to help each other is amazing. The challenge is to find ways to tap into this energy in order to help us all live better with less. This is true both of western economies and of those countries that are already living with less.

What binds us all together is hope… hope that success lies ahead. Even in the darkest of times and in the poorest of countries, life breeds hope. The drive for a better life, be it through work, education, family, or faith, is universal.

3. Tourism offers hope.

For better or for worse, the impact of tourism on local societies and economies is huge. Maybe it’s the perspective of a traveler, but for so many countries, from Europe to Asia, tourism is seen as an economic panacea. We saw an endless stream of new hotels being built throughout India, Nepal, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Tourist dollars are the great hope, and indeed Western money is the best way out of poverty. Tourism accounts for 9.8% of the global economy, according to the World Travel and Tourism Council. On the positive side, it helps redistribute wealth while expanding minds, but tourism can be fickle and is an early casualty in a global economic downturn. The best examples we saw used tourism revenue to support long term community development and environmental protection.

4. A strong voluntary sector is crucial.

Healthy and resilient societies have strong voluntary organizations. We saw this in Udaipur, India, where Shikshantar is training people to become part of a diverse local economy; in Siem Reap, Cambodia, where the Cambodian Landmine Museum and Relief Centre supports effort to clear old landmines and support victims; and in northern Vietnam, where Sapa O’Chau is a social enterprise linking tourism to community development. Groups and social enterprises are a voice of social values and aspirations, they address needs, they empower voluntary change, and they create the space and opportunity for political and business leadership. Social organizations can also be a check against power, and unfortunately the ability to organize for change is under attack both in democratic and totalitarian countries alike at a time when it is needed the most.

5. Culture is everything.

Culture is the foundation of who we are. It influences our behaviour and how we respond (or fail to respond) to environmental issues. It can be our competitive advantage, or the millstone preventing change. The ability to invent, develop, and implement new approaches is wholly dependent upon the ability to nurture a culture of change within each country.

The issues are complex, and the answers are never easy, simple, or universal. The carpet of plastic we saw on roadsides across India and Southeast Asia would not be possible were it not the cultural norm to toss what was once organic and biodegradable waste aside to be food for animals. Yet, we also found that road rage is virtually non-existent in the crush of traffic on Indian and Asian streets, and that France has a remarkably more progressive cultural outlook on transportation than Canada.

ONE INSIGHT

The common thread is the realization that people are at the heart of our ability to find more sustainable solutions – not corporations or governments. Culture establishes norms and presents both barriers and opportunities; organizations build common cause and strengthen entire communities; and people can be the individual spark for change or part of a collective force for change (for better or for worse).

Understanding that people and culture are at the heart of the issues and solutions carries profound implications for both environmentalism (the fight against destruction) and sustainability (efforts to promote corporate responsibility and voluntary leadership).

The piece that is missing is to put people first. For fairly obvious reasons of funding and profit, social sustainability has never received as much attention as economic sustainability, but if we are serious about achieving results it should.

Sustainability should start with the hopes and aspirations of people and seek to meet them through less disruptive means. In short, we need to help people live better with less, a mantra that works equally well in poor countries as it does in the opulent. The challenges for each country are unique, but they all reflect the basic requirements to quality of life: shelter, food, energy transportation, community, and jobs.

On the international stage, there is hope. On September 25th, 2015, 150 world leaders at the United Nations Sustainable Development Summit will be asked to adopt 17 sustainable development goals, a dramatic increase from the eight Millennium Development Goals of 2001. The implementation of these goals around the world is the opportunity we need to connect global goals with the needs and aspirations of people.

Somehow, in each individual country, we need to transform global goals for the health and sustainability of our planet into policies and programs that will give people hope for the future.

FIVE IDEAS

Implementing global agreements is no simple matter. While in Rome, we met with Thomas McInerny, whose organization, the Treaty Effectiveness Initiative (TEI), seeks to improve the on-the-ground implementation of the over 600 global agreements that have been adopted in the past 70 years. Agreements can become mired in politics, bureaucracy, corruption, and lobbying, so it is important to have strong tools for transparency, accountability, and effectiveness.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, we chanced upon Paul Forest and John Smith Gumbula in the small town of Bellingen, Australia, where they are developing Cluster, a new organic approach to internet-based organizing around values and action. Whether organized or organic, it’s going to take tremendous efforts to translate global ideas of sustainability into ideas that will help people live better with less.

Drawing from our experiences and the above lessons, I can offer five ideas. Each one is simple, yet radical: simple in that we can do it, and radical in that they require a radical shift in the way we approach the transition to a sustainable economy and society.

1. Rethink sustainability.

Honesty about the unsustainable nature of our current economy is critical, and altogether missing from the discussion of our economic and social future.

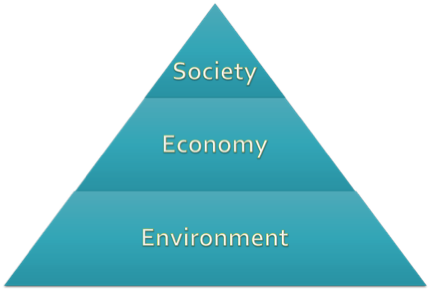

We need to change how we look at sustainability – right down to the imagery we use to represent the relationship between environment, economy and society. The mistake was to think of it as a compromise between development and protectionist goals where each aspect carries equal weight. Sustainability is not about balancing profit and protection, it is about ensuring a solid and stable foundation to permit economic and social development.

We should think of sustainability as a triangle, or pyramid, with the environment and resources as the foundation upon which economic activity is possible. The economy, in turn, provides the potential for social development. Without the natural environment and its resources, the economy and society will collapse.

The second aspect of rethinking sustainability is to measure it. True sustainability is the ability to maintain an activity indefinitely without impacting the resource base or natural environment. Here’s an idea that came to me while on a Red Dao farm in Vietnam: S=D/I (Sustainability is defined as the Durability of a product or process divided by its environmental Impact). Indigenous cultures, such as Australian Aborigines lived for 40,000 years without significant impact – score 40,000. The terrace farming we saw in Northern Vietnam, has been sustained for hundreds of years – score 500. The plastic wrappers we saw littered across those same rice paddies have a use of less than a year and an impact that lasts hundreds – score 0.002. You can tweak the factors and develop more rigourous tools to quantify the impact, but it’s hard to fudge the results. Try it yourself on oil and nuclear versus wind and solar; on clear-cut forestry and palm oil plantations versus community forests, or on bikes and transit in urban villages versus cars in suburbia. In a world where every major corporation produces a sustainability report to promote their environmental commitment, we need a simple formula and arm’s length reporting to remind us of the distance we have yet to travel to achieve a sustainable future.

2. Start with Values.

The transition to sustainability will require substantial changes in how we live, especially those of us in the western world. This change will happen either through crisis (environmental or economic) or by choice. If we want it to happen by choice, and we do, then we need to act sooner rather than later and focus on changes people want.

We need to start with the core values that unite us as a community or country, and translate them into solutions that make us feel good about ourselves and improve our quality of life at the same time as they increase sustainability and reduce our carbon footprint. This is common sense, but it would mark a departure from the current emphasis on economic growth and profit coupled with government austerity as the key drivers of social policy.

3. Set the Agenda.

Social organizations need to lead the way in defining social values, not government or corporations. This is far more involved than building a coalition of organizations to lobby for government policy. It requires collaboration between organizations not just to define the future we all want, but to be leaders in delivering the change.

From my past work with the Conservation Council of Ontario, I know this approach can work. Imagine the power of a national or regional sustainability agenda, backed up by community action plans across the country, that seek to engage and empower people and groups in adopting solutions that improve their quality of life and reduce our environmental impact.

4. Invest in our Future.

The transition to a sustainable future needs funding. We can choose to squander our current economic and resource wealth, or we invest in a sustainable future. Those countries that have used the profit from resource development and consumption to invest in sustainable infrastructure and community development are way ahead of the game.

In our travels, we saw both local and national examples of resource-based funds, such as the Chitwan National Park in Nepal, where half of the park user fees support local community development, and Malaysia’s national oil company whose revenue amounts to 45 percent of the national budget. At a time when the world is struggling to find ways to address both climate change and sustainability, the lack of resource-based transition funds (such as a climate fund) is appalling.

5. Have Faith.

Perhaps the most surprising lesson learned on our trip was the power of faith, not so much the undeniable wealth and power of religious institutions, but the power of small faith. The Buddhist prayer wheels and the daily offerings to their gods and ancestors in Bali were just two examples of daily rituals that people to live according to their values.

Offerings on a rusty bridge in Ubud, Bali

Given that the predominant and most dangerous cultural trend in the West has been a growth in isolationism, protectionism, anger and hatred, we could all use a simple daily act of self-awareness to remind us to live a good life, to be kind to others, and to respect the environment. As we travelled, I followed a blog series by a friend and writer, Lorne Blumer, on the Birkot HaShachar, the Jewish morning blessings, and the role they might play in helping us – Jews and non-Jews; believers, agnostics, and atheists – live with more gratitude, presence, and even compassion.

A daily ritual of awareness, whatever form it takes, reminds us of our values, and to make the most of our lives and of each day.

EPILOGUE

Now I am back home in Canada, I am asking myself, can we implement this approach here? Can we rekindle our nation’s commitment to leadership in social sustainability? Can we find the leadership, vision, and tools to guide Canada over the next century? Canada has a proud history and culture as a compassionate country. We can and should be a leader in new approaches to sustainability.

Certainly, everything I wrote about last year in The Next Wave has been reaffirmed and strengthened through the year of travel. The time is nigh for a new wave of leadership in supporting a voluntary transition to a future of our choosing: the future we want.

Here are five things we could use in Canada – key signs of leadership based on implementing the United Nations goals for sustainable development:

- A public vision of the future we want, a coalition of senior organizations across Canada to translate the UN sustainability goals into a Canadian vision and a national voluntary sector plan of action and leadership.

- Federal, provincial, and municipal sustainable development strategies to mirror and implement the UN sustainable development goals in Canada.

- Community action plans: a commitment from every municipality to support local groups and volunteers through a community network and action plan.

- Renewed international aid: a new federal commitment to support the sustainable development plans of developing countries through transparent and accountable processes.

- Transition funds: resource or carbon-based funds to ensure that a significant portion of Canada’s wealth is used to invest in the future we want.

- Beautiful ideas: innovative and integrated solutions that address multiple goals.

Each one of the first five tasks is a major challenge, but we cannot hope to even come close to a sustainable future unless we learn to think big, and cooperatively. The last one is organic, the opportunity for all aspiring entrepreneurs, social ventures, and activists to come up with solutions to help us all live better with less.

Sustainability has to start at home. Time to step up our game, Canada.

The former executive director of the Conservation Council of Ontario, Chris has started a new initiative to help Canada transition to a sustainable future by “living better with less,” Canada Conserves. After 30 years in the environmental movement, Chris Winter is on a well-deserved round-the-world sabbatical with his family. Along the way, Chris will be sharing examples of how other countries are dealing with climate change, resource scarcity and economic turmoil. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook. You can also follow the family’s Hello Cool World tour blog.