<

Video docu-game? Interactive sim-erendum? The future of journalism? How about democracy?

The producers of the free internet-based media confection Fort McMoney probably have aspirations to all of the above. To this admittedly crusty veteran from the days of news film and teletype, the answers are more like yes and sorta for the first two. But the future of journalism, let alone democracy? Let’s hope not.

Open Fort McMoney’s first screen and you find yourself driving along a winter highway. You’re at “the end of the road, and the world’s edge,” a voice heavy with omen informs you. “You’re about to embark on a game.” But in this game, “everything is real.”

Your mission is to visit, explore, discuss and vote on the future course of the city of Fort McMoney – played by the actual city, citizens and transient workers of Fort McMurray, Alberta – as it pursues its civic goals against the raw-octane economic forces of an industry for which cash is no object and people are a commodity. “Fort McMoney’s fate is in your hands,” you’re told.

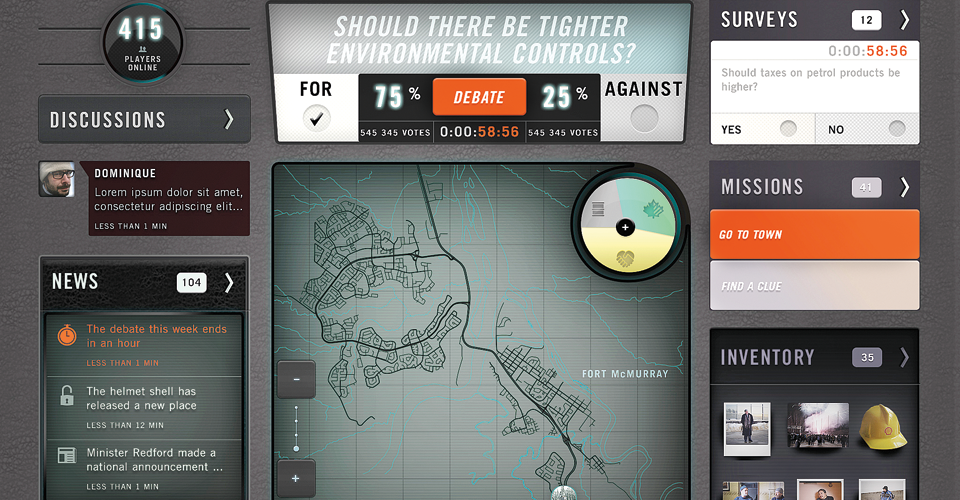

‘Playing’ the game entails watching bits of connective video that lead to opportunities to ‘question’ various real Fort McMurray personalities. In the first episode, these run from a dumpster-diver who claims to earn $50,000 a year just from Fort McMoney’s garbage, to the town’s mayor, Melissa Blake, who delivers responses in a Siri-like dialect of bureaucratese. A ‘control panel’ provides a pause button and windows to debate and vote on propositions like raising taxes on petroleum (the pro-tax side was winning with 86 per cent at the time of writing).

Evidently, if I ‘asked’ enough questions – really, clicked on enough pre-recorded video responses behind short question menus – I would earn ‘influence’ points in these debates. I don’t really know. I was never able to play Fort McMoney long enough for this feature to become apparent. Not for lack of trying.

Director David Dufresne’s creation – in which the oil sands’ increasingly heavy footprint on the physical and social health of those living on their expanding periphery is revealed over episodes of play – is an admirably ambitious undertaking in a genre of storytelling so new it’s still searching for a name. Other examples include The New York Times’ chilling account of a fatal avalanche and the NFB’s own, smaller and more lyrical The Last Hunt.

It’s to the NFB’s credit that its historic pioneering spirit in film has evolved to support form-busting ideas like these. But Dufresne’s excellent effort is brought down by technical challenges. On the four different occasions I tried to play it, the game’s technological grasp didn’t quite achieve its reach, and I was left virtually shivering in a cold parking lot, unable to prompt the ‘interactive’ imagery to take me to the promised next step.

More seriously, Fort McMoney’s sophisticated format was not matched by its analysis. “Should oil be nationalized?” one referendum inquired, a question so vaguely put – Oil in the ground? Oil companies? Gas stations? – as to be all but meaningless.

But those are quibbles. Future productions in this nameless genre will ask better questions. I have a deeper problem. It is the matter of efficiency.

The production budget for Dufresne’s documentary game ran to a reported $870,000. That bought 48 weeks of development, two months on location (in winter!) to conduct interviews, and five more months of post-production.

The result is an intriguing new way of storytelling that combines the visual potency of conventional documentary with the open-ended asides that hyperlinks allow. It engages the idioms of gaming, choice and first-person control, which for many is the language of the stories they’ve imbibed since babyhood.

That control is a deception of course. The choices that count in this story – whom we’ll question and what they’ll have to say; the selection of audio clips of the local radio station; the flashback archival newsreel – have all been made for us, just as they were by the crudest ink-stained wretch when he sent his final copy to print.

That these choices are not accidental – how could they be? – is incidental. What’s distressing is that for all the vast expense of their acquisition and elaborate packaging, they say so little more than anything else an interested reader or web-surfer could easily know already about Fort Mac and the oil sands.

I applaud the (almost) dazzling advance in craft. But Fort McMoney is a dazzling elaboration only of medium – its message is old news. As a citizen, I question how many Canadians it brought or will bring closer to acting on what that knowledge means.

And as a journalist, I know that $870,000 buys an awful lot of essential reporting that isn’t dressed up in gameplay.

Fort McMoney. David Dufresne (creator), Canada: Toxa Inc. & the National Film Board, 2013. | fortmcmoney.com

Reviewer Information

Chris Wood, is an author, speaker and journalist. He first wrote about the environment in the 1970s, winning awards for his coverage of nuclear power and agrochemicals. His most recent book, Down the Drain: How We Are Failing to Protect Our Water Resources (2013), written with Ralph Pentland, details how successive federal governments have neglected Canada’s water and proposes new thinking to instigate change. Wood, his wife and their two bull terriers live in Cuernavaca, Mexico.