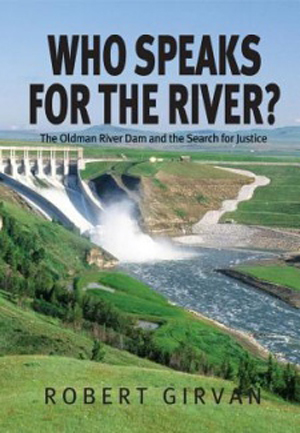

When Robert Girvan began to research the dramatic events around the Oldman River Dam controversy and the resulting 1992 Supreme Court of Canada decision, Friends of the Oldman River Society v. Canada (Minister of Transport), he could not have foreseen how much his book would resonate, nearly two decades later, with the environmental and Idle no More movements.

When Robert Girvan began to research the dramatic events around the Oldman River Dam controversy and the resulting 1992 Supreme Court of Canada decision, Friends of the Oldman River Society v. Canada (Minister of Transport), he could not have foreseen how much his book would resonate, nearly two decades later, with the environmental and Idle no More movements.

As a criminal defence lawyer and former Crown prosecutor, Girvan’s passion for courtroom drama is revealed through painstaking accounts of the dichotomous legal proceedings. At the same time as the Friends of the Oldman River (FOR) launched court challenges against the Alberta government’s construction of the dam, Milton Born With A Tooth galvanized a contingent of the Piikani First Nation – the Lonefighters – to resist inundation of their sacred ancestral burial grounds. Upstream from their reserve in the picturesque Oldman River valley in southwestern Alberta, the Lonefighters attempted to divert the river by bulldozing a culvert. A confrontation with the RCMP culminated in Born With A Tooth being prosecuted for, among other offences, discharging a firearm. Girvan explains the legal complexities in layperson’s terms, spawning a reader-friendly exposé of a defining period in Canadian history.

Girvan traces the saga to 1877, when the Piikani First Nation became bound by Treaty Seven, and then to 1919, when farmers in Southern Alberta formed the Lethbridge Northern Irrigation District (LNID) in order to take water from the Oldman River. He chronicles then-premier Peter Lougheed’s 1984 announcement that the Alberta government would dam the Oldman River, and succinctly summarizes the ensuing dissent. Girvan notes that “[N]either the Piikani, nor the landowners who would lose their homes in the river valley areas to be flooded were told of the decision before the public announcement.” Indeed, the dispute paved the way for enshrining in law the government’s duty to consult with First Nations when making decisions that might impact lands and resources subject to Aboriginal claims.

This is a character-driven narrative, populated with colourful actors – farmers and founding members of the LNID, journalists, environmentalists such as Martha Kostuch, and archeologists like Brian Reeves. There is a large cast from the judiciary and environment ministry, as well as members of the Piikani First Nation and RCMP officers dispatched to the site of Milton Born With A Tooth’s standoff.

Girvan’s style of writing can best be described as nostalgic, yearning for a period in recent history when more Canadians stood up for their beliefs. This idealistic mindset is most dynamically revealed when he recounts a wilderness concert – the Happening – that many Albertans likened to Woodstock. Organized by FOR to create public awareness and galvanize opposition to the dam, the Happening drew thousands of Albertans, along with musicians Gordon Lightfoot, Murray McLaughlin and Ian Tyson, and special guests David Suzuki, Andy Russell and tribal elder Joe Crowshoe. The protesters converged upon Maycroft, a recreational area upstream from the pristine 40-kilometer stretch of river valley earmarked for the dam site and reservoir, where three rivers – the Oldman, Crowsnest and Castle – merge.

Girvan portrays all players as driven to advance their own interest in relation to the river, including the Alberta government, which he documents as having flouted the law at every juncture. By the time the Supreme Court ruled in favour of FOR and sanctioned federal oversight of dams, bridges and other infrastructure such as pipelines, the dam was nearly completed. A generation later, the federal government’s 2012 budget overhauled the Navigable Waters Protection Act, rendering the Supreme Court’s ruling on the issue moot. Federal environmental assessments are now restricted to industrial developments that impact bodies of water with commercial, recreational or Aboriginal fisheries. Since the Oldman River has no such fishery, a similar development today would not result in a court-ordered environmental assessment.

Notwithstanding, Girvan’s book is a testimony to the legislative environmental safeguards that once existed and are still possible in Canada. In the present context of the Harper government’s obsession with winning US President Obama’s approval of the Keystone XL pipeline, the conflicts documented in Who Speaks for the River? are harbingers of a political agenda that facilitates resource extraction and industrial development at the expense of our natural environment and the interests of First Nations. Girvan’s narrative should inspire environmental and Aboriginal movements to advance a unified front against short-sighted government policies and a precarious future.

Who Speaks for the River?, Robert Girvan, Markham, Ontario: Fifth House Ltd., 2013, 392 pages.

Reviewer Information

Barbara D. Janusz is a lawyer, educator and author of the novel Mirrored in the Caves. She has published environmentally themed book reviews, opinion and analysis columns, creative non-fiction stories, essays and poetry in journals, magazines, newspapers and anthologies across Canada.